EAST LANSING, MI – A small butterfly, once a common sight on the prairies of the Midwest, has suddenly vanished and is now the focus of an international partnership racing against time to save it from the brink of extinction.

“Just how quickly they disappeared is what’s really the alarming thing,” said David Pavlik, a research assistant with Michigan State University.

Pavlik is part of an international coalition of scientists and conservationists working to save the Poweshiek skipperling (pronounced POW-uh-SHEEK), an inconspicuous orange butterfly that was once so common in the prairies of the Midwest that collectors largely ignored it.

Now “there are more giant pandas in the world than there are Poweshiek skipperlings,” Pavlik said.

They were once found from the prairies of Manitoba through Minnesota, the eastern Dakotas, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana and into Michigan. Now they have disappeared from all but two places at the extremes of their once-extensive range – Manitoba and southeastern Michigan.

The butterfly’s population crash was so sudden that biologists weren’t sure what plants the butterflies or their caterpillars needed to survive or what caused the decline in the first place.

The partnership is now working to raise the butterflies in zoos for release back into the wild and restore the natural habitats where they once thrived to ensure their long-term survival.

What happened to the Poweshiek skipperlings?

Cale Nordmeyer, a conservation specialist at the Minnesota Zoo, said the Poweshiek skipperling was common when he was growing up in Minnesota.

“As a tallgrass prairie specialist, it really thrived in the mesic prairies, in Minnesota and elsewhere here in the upper Midwest,” he said. Mesic prairie is a type of tall grass prairie, a native grassland that once flourished throughout the Midwest.

“If you were out in the right prairie at the right time of year, you were going to see Poweshiek skipperlings,” Nordmeyer said.

That started changing about the year 2000, when researchers noticed they weren’t seeing them as much anymore.

But when the Minnesota Zoo wanted to study them, researchers could not find any Poweshieks left at the sites they expected them to be.

“Sometime between 2009 and 2012, it looks like we lost all of our Poweshiek skipperling sites in Minnesota,” he said. They also disappeared from most of the rest of their range.

“Suddenly, these last couple of little populations, many of which were never that big here in far eastern Michigan, suddenly became incredibly important,” Nordmeyer said.

It isn’t obvious why they disappeared, he said. He and other biologists are still trying to understand what happened, what the threats are and what the solutions might be.

Pavlik said it’s likely a combination of reasons.

“Habitat loss historically is a huge one,” he said. “The species requires tall grass prairies and prairie fens here in Michigan.” Prairie fens are rare and unique grassy wetlands that are fed by groundwater instead of creeks or streams.

“Over 99% of that habitat is gone,” he said.

Additionally, he said widespread aerial spraying of insecticides has affected the last remaining strongholds of the butterflies, and climate change is probably contributing as well.

“The species overwinters as a caterpillar, and so they can be especially susceptible to changes in winter climate. So it’s got a lot going against it,” he said.

One indication that insecticides could be a major factor in their disappearance is that the remaining sites where they’re still hanging on are buffered from agriculture by woodlots or grassy fields, he said.

Adding to the difficulty, the butterfly disappeared so quickly researchers weren’t even sure what exactly they need to survive, including which plants they feed on.

Learning what the Poweshiek skipperling needs to survive

“They seem to have two major nectar sources,” Pavlik said, referring to the flowers adult butterflies feed on.

“And that’s black-eyed Susan – which seems to be their favorite – and then shrubby cinquefoil,” another relatively common yellow prairie flower, he said.

The butterfly’s caterpillars, on the other hand, have been found on prairie dropseed, a fairly common prairie grass, and on a rarer grass called mat muhly. Both occur in high-quality native prairies and in prairie fens.

However, Poweshieks have been found in areas without either of these grasses, so biologists suspect the caterpillar feeds on other grasses or sedges as well. What those are is not known.

When biologists realized how precipitously the Poweshiek skipperling was declining, they convened a meeting of researchers and conservation partners, said Tam Smith, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the national recovery lead for the butterfly.

The experts at the meeting “recognized that (the Poweshiek) was going down this spiral of extinction,” Smith said.

The species was officially listed as a federally endangered species in 2014, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

In 2022, the agency released a 50-year recovery plan for the butterfly, listing the actions scientists had determined were necessary for its full recovery. The cost for all activities over the five decades was estimated at just over $57 million.

One of the main proposed actions at the meeting was to start a captive breeding program.

Smith said the Minnesota Zoo stepped in first to start rearing the butterflies in captivity, using eggs that had been collected from females in Michigan.

But with so much uncertainty about the basic biology of the species, it was difficult going at first – they quickly found out how sensitive the species was to temperature and humidity, Smith said.

“One of the first years they started, the temperature was off,” Smith said. That caused the caterpillars to develop too quickly.

“And so, it just didn’t work that year,” Smith said.

Later a zoo in Canada, Assiniboine Park Zoo in Winnipeg, joined the effort, and a few years after that John Ball Zoo in Grand Rapids, Michigan, helped as well, Smith said.

Rearing baby butterflies at John Ball Zoo

“Our prairie butterfly program here at the zoo has just grown enormously since 2020,” Bill Flanagan, the conservation director at John Ball Zoo, said.

The goal is to “make lots of baby Poweshieks so we can do releases and bolster those wild populations to the point where we can start to do reintroductions and start to recover the species,” Flanagan said.

The first caterpillars arrived in 2021 from the Minnesota Zoo, he said.

“We turned 32 caterpillars into somewhere in the neighborhood of 150 caterpillars” the next year, Flanagan said. “The next year, (in 2023,) we had something like 500 caterpillars in the program.”

It was a close call – in 2022 only nine Poweshieks, the lowest number ever, were observed in the wild in Michigan, Pavlik said.

But given the success of the zoos’ captive rearing programs, biologists were able to release more than 100 butterflies that year, just in the nick of time.

And in 2023 they saw more butterflies again.

In 2023 they had bred enough butterflies to release more than 500, and in 2024 and 2025 more than 1,000 each year.

That is “by far the most that these programs have ever had,” Pavlik said.

In case the wild populations crash, the zoo does not release all the butterflies it rears into the wild each year, instead holding some back for continued breeding, Pavlik said.

Nordmeyer said if zoos had not already started breeding the butterflies before the population nearly disappeared in 2022, there may not have been enough of them to build the population back up.

Because the number of butterflies was so low when the breeding program started, there is a danger of inbreeding. That’s why scientists track each Poweshiek’s family tree to make sure closely related butterflies don’t mate.

Tracking butterfly genetics

“We know how all the butterflies in the zoos are related to each other,” Nordmeyer said. “It allows us to do a good job conserving what little genetic diversity is left.”

If the genetic diversity drops too low, the butterflies may not be resilient enough to survive over the long term, he said.

“That’s why the genetics become really important,” he said.

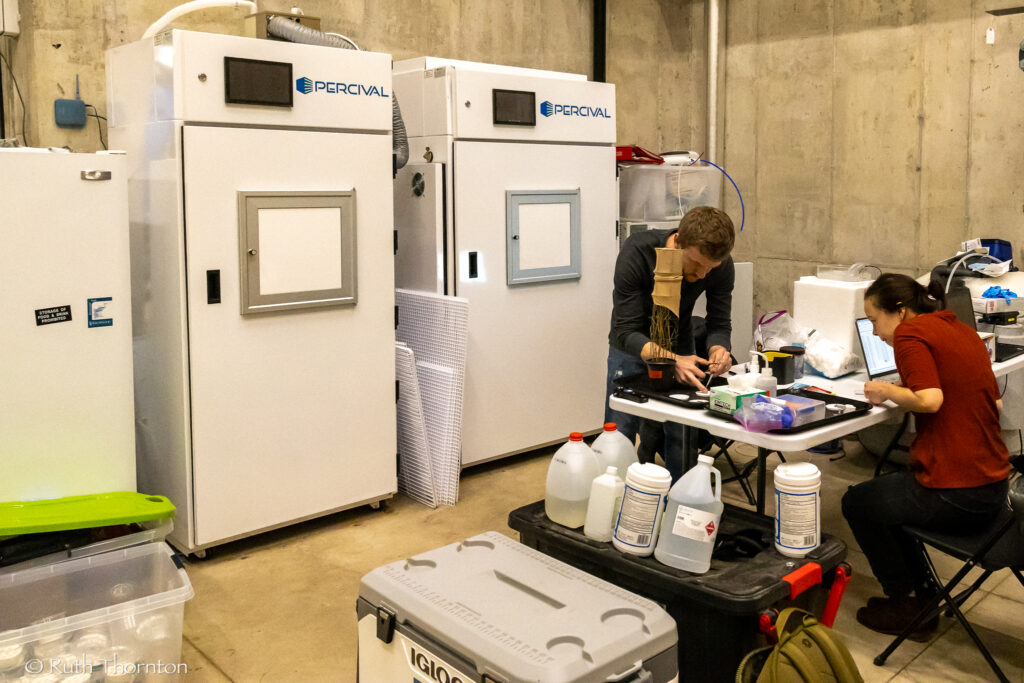

Sarah Fitzpatrick, a conservation geneticist at Michigan State University’s Kellogg Biological Station, said she is sequencing the entire genome of the remaining Poweshiek genetic lineages – or family trees – at John Ball Zoo and in the wild.

“Then we joined forces with the Canadian partners at Assiniboine (Park Zoo), who have a similar data set for their Canadian butterflies,” she said.

That enabled the biologists at her lab to determine how closely related the butterflies from different areas are and choose which to breed. That maximizes the genetic diversity and gives their offspring the best chance of survival.

It’s important to not breed butterflies that are either too similar or too different from each other genetically. That can lead to unintended consequences and could do more harm than good, she said.

As expected, they found some genetic differences between the Michigan and Canadian populations, but not so much to alarm them or prevent being able to cross them with each other.

Results also showed that the Michigan populations were slightly more inbred than the Manitoba butterflies. “That is consistent with what we know about the population sizes that are left,” she said.

She said in the future they may try crossing butterflies from Canada with Michigan ones to increase their genetic diversity.

But before the offspring of those crossings could be released into the wild, biologists would raise them in captivity first to make sure they are healthy and can produce healthy eggs and offspring of their own.

Interestingly, Poweshieks in one particularly large prairie site in Michigan that were on opposite ends of the area also showed slightly different genetics, indicating that they were not as closely related as expected.

Fitzpatrick said that could indicate that the butterflies don’t fly very far and that habitat fragmentation may be more detrimental to them than for other butterfly species that fly farther.

Getting the timing right between zoo-reared butterflies and wild ones

Besides making sure the genetics of the zoo-reared butterflies are compatible with wild ones, zookeepers also have to ensure caterpillars raised in the zoo become adult butterflies at the same time as those in the wild.

If that timing is off, the two groups would not be able to mate and produce offspring. The timing also has to match when the flowers they feed on are in bloom.

After mismatches during the first couple of years at the Minnesota Zoo, that timing has improved.

“The last few years we’ve been really successful,” Pavlik said. “The first butterfly is usually seen out in the wild the same day or within a day of when our butterflies are coming out.”

That enables the captively reared butterflies to mix seamlessly with the wild populations, “which is always the goal. We want them to mix,” Pavlik said.

Breeding butterflies: a year at John Ball Zoo

With a short flight period of only a few weeks, things get hectic at John Ball Zoo in July, when the adult butterflies emerge and start laying eggs.

“We have one shot,” Pavlik said. “In three weeks we have to do all of the breeding, all of the releases. It’s a pretty crazy time.”

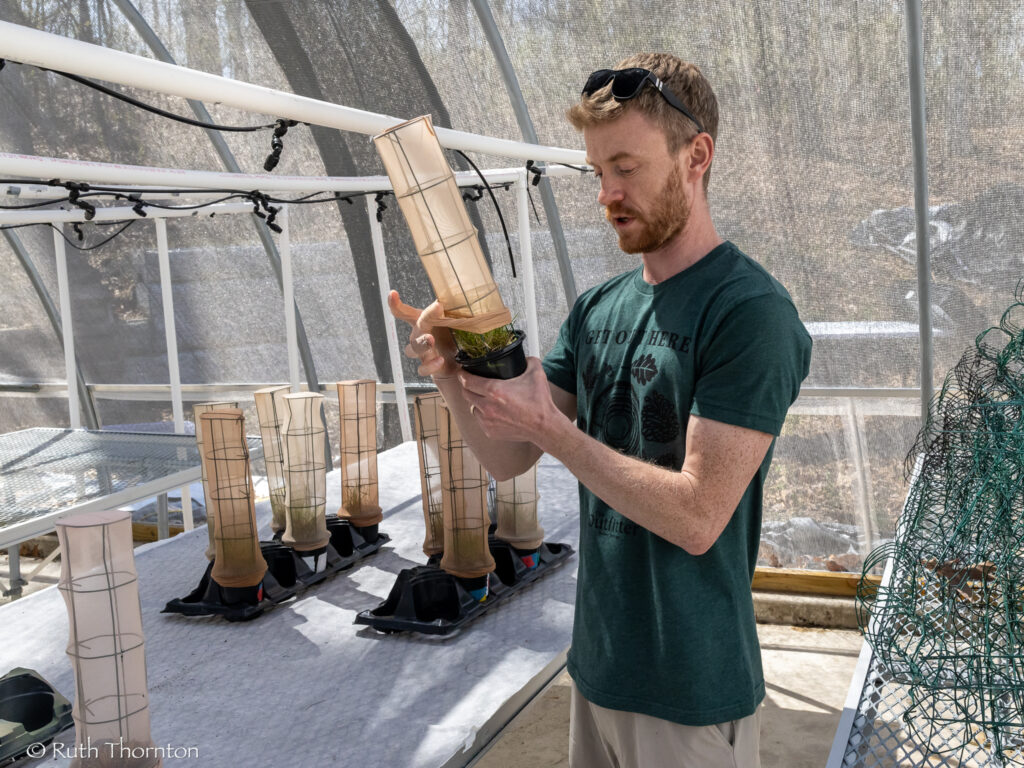

After the adults emerge, biologists pair up a male and female butterfly – first making sure they are compatible genetically – and place them in what they call a “breeding tent,” a sheer cloth-covered square frame about 12 inches to a side.

Then “we monitor them throughout the day to see if they do breed,” he said. “And if they do, we’ll release the male into the wild the next day, and then the female gets transferred to an egg laying enclosure, where she’ll lay the eggs that we’ll collect every morning.”

Almost every morning someone from the zoo drives the newly hatched butterflies to southeastern Michigan, a couple hours’ drive away, for release into the wild, Pavlik said.

“Every month of the year, we’re doing something different for the species,” Pavlik said.

When people think about butterflies, they often picture the adults that they see fluttering from flower to flower. But many species fly for only a couple of weeks during the year, including the Poweshiek.

Each butterfly lives for only about four to six days in the wild, he said. “Most of the year, we’re taking care of the caterpillars.”

It takes about 10 days for eggs to hatch, according to the Michigan Natural Features Inventory (MNFI).

The caterpillars – also called larvae – feed on the host grasses and go through several “instars,” progressive stages where they shed their skin and grow. Eventually they enter what’s called a “diapause” and overwinter, resting head-down on grass blades.

When they wake up in the spring, usually around April or May, they resume feeding and go through additional instars before finally turning into the familiar butterflies, according to the MNFI.

The zoo recreates the natural conditions as best as it can, transferring the caterpillars to a freezer during their diapause stage.

“When winter comes, we’ll take those caterpillars off of the plant and put them in a very special and highly controlled overwintering chamber where we can control the temperature and the humidity for exactly what the species needs to survive for nearly six months,” Pavlik said.

During that time, the caterpillars do not move or eat.

In the spring, when the host plants start growing again, zookeepers bring the caterpillars out of the freezer and put them back on their plants.

“From May until the end of June, we’re taking care of those caterpillars again until they become adult butterflies,” he said. “And then we repeat the cycle all over again.”

Protecting the butterfly’s remaining habitat

For releases to be successful, it’s vital that their habitat in the wild is still in good shape.

“It doesn’t matter how many butterflies we can produce here at the zoo, we could release 5,000,” Pavlik said. “But if the habitat is not there for them, or if the habitat’s been taken over by invasive species, it doesn’t matter how many we release, it’s not going to work.”

He said that’s why the international partnership is so important – various organizations working on different parts of the problem.

“I don’t think I’ve heard of a butterfly that has this big of a coalition of people working to save it from extinction,” Pavlik said.

Members of the coalition include not only federal and state agencies from the U.S. and Canada, but also universities, nonprofit conservation organizations and land managers maintaining and restoring the natural areas the butterfly needs to survive.

Last year marked the first attempted introduction of the butterfly in Michigan at a site where they once occurred but had disappeared from.

The site had become overgrown with buckthorn, an invasive woody species that quickly takes over grassy areas, including prairies and prairie fens.

Nordmeyer said land managers in southeast Michigan had spent five years removing the buckthorn and other invasive species from the area.

The land managers “clear(ed) out the woody vegetation, bringing in seeds to really make the characteristics of that land back to what historically was grassland fen habitat so that it could support these butterflies once again,” he said.

The locations where the butterflies still occur and where they are released are kept secret, however, because of incidents in the past few years when people trampled the fragile habitat when the butterflies were flying.

Smith said she thinks the “events were largely amateur or semi-professional photographers that I think had good intentions.”

“They want to go out there and see this extremely rare butterfly and take some really great photos. But the habitat is so fragile and small that we try to limit the number of folks that are out there,” she said.

With such low population numbers, Smith said, any trampling of eggs or caterpillars, or chasing away the adult butterflies, could be devastating for the species.

Signs of a larger problem?

The decline of the butterflies is a warning sign that the natural areas it occurs in could be in trouble.

“It’s a really good indicator species,” Pavlik said. “When we see these declines happening for a butterfly so quickly, we know that whatever is affecting that species is probably affecting a lot of other species.”

“It’s important to know that it’s not just Poweshieks,” he said. “Pollinator and insect declines are happening very quickly worldwide.”

Many other species depend on them, Pavlik said.

“That’s part of the reason why their survival is so low in the wild, they are a very important part of the food chain – caterpillars and butterflies in general,” he said.

Spiders and parasitic flies eat the caterpillars, and dragonflies and birds eat the adult butterflies, he said. “They provide vital food for the entire food chain.”

For example, the decrease of bird populations has been tied to the decrease in pollinators and butterflies, he said.

A promising recovery amid an uncertain future

People can help protect the Poweshiek skipperling and other pollinators, Pavlik said.

“If you want to get involved and do something that can have a positive impact for (pollinators), plant native species,” Pavlik said. “It’s not just the Poweshieks that need the help.”

“If you plant native pollinator gardens in your yard, you’ll be helping so many other species. And don’t spray pesticides,” Pavlik said. “Those are two of the biggest things you can do to have a positive impact for pollinators across the world.”

While the Poweshiek skipperling is not out of the woods yet, preliminary results from this year’s field season are promising, Nordmeyer said.

“We were able to confirm survivorship of last year’s offspring at the (reintroduction) site,” he wrote in an email.

The situation for Poweshieks is still dire, he said, but this year biologists saw more butterflies than in recent years, and a similar number as before the 2013 population crash.

“It’s too early to declare victory,” he said, but thanks to the hard work of the partnership working together to propagate the butterfly and restore its habitat, “the downward trend of the Poweshiek skipperling is tangibly reversing.”